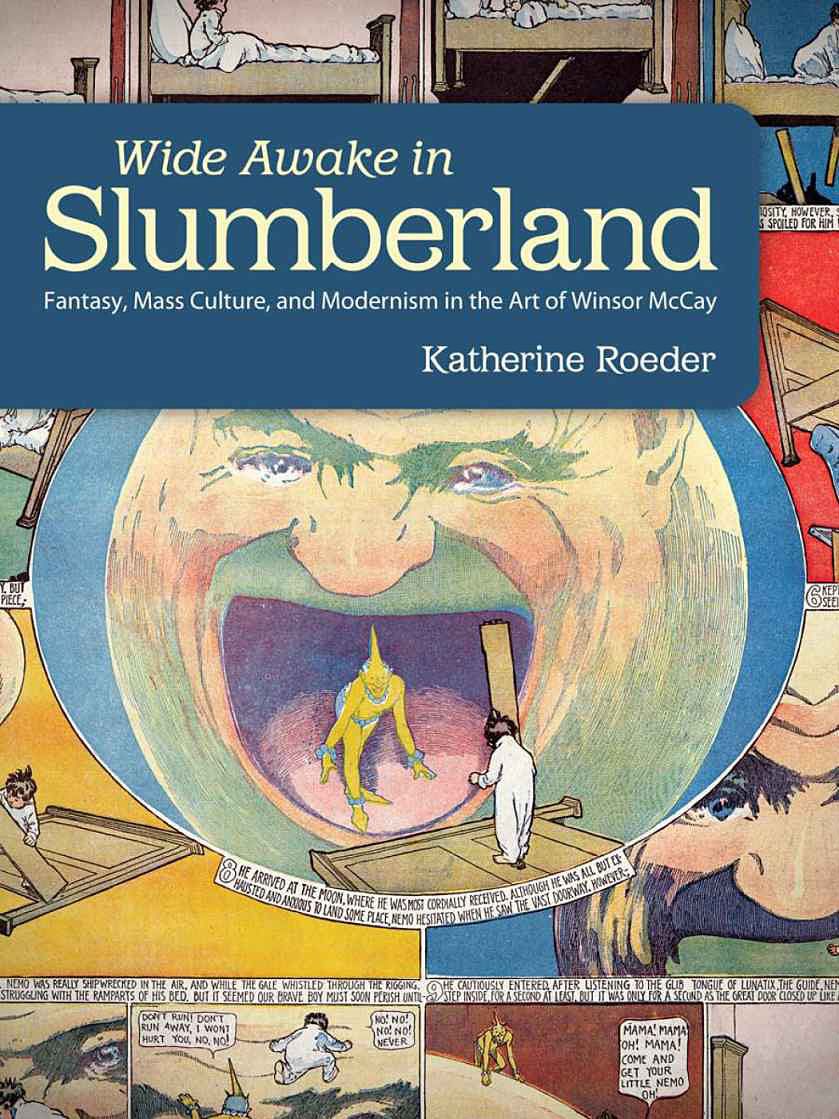

Wide Awake in Slumberland Fantasy Mass Culture and Modernism in the Art of Winsor Mccay

Winsor McCay has long been considered one of the masters of comics, and this twelvemonth there is increased attention on his work. This fall, Locust Moon Press is publishing "Little Nemo: Dream a Little Dream" with more than one hundred creators taking crafting broadsheet-sized strips, while Eric Shanower and Gabriel Rodriguez are offering their ain take on the character in IDW'south "Footling Nemo: Return to Slumberland" miniseries. A new book about McCay offers some answers as to why he remains such an important effigy fifty-fifty lxxx years after his death.

Katherine Roeder is a offshoot professor at George Mason University and has written essays for "The Comics of Chris Ware" and "A New Literary History of America" in addition to "The Comics Journal" and "American Fine art." An art historian past training, the University Press of Mississippi has recently released her first volume every bit part of their Great Comics Artists series. "Broad Awake in Slumberland: Fantasy, Mass Culture and Modernism in the Art of Winsor McCay" looks at the creative person known for "Little Nemo in Slumberland" and places him in the context of popular civilization at plow of the century America, drawing on many sources from exterior of comics including vaudeville, poster fine art, early cinema, photography and motion studies and transformed comics forever.

Roeder spoke with CBR News from her home in Virginia to talk well-nigh the intersections of art and comics and civilisation, why McCay remains such an of import and interesting creative person, teaching comics and doing research in comics at the Library of Congress.

CBR News: You accept a degree in art history. What first fabricated you interested in studying comics?

Katherine Roeder: I was interested in comics since I was a kid. I have fond memories of reading "Flower County" and "Calvin and Hobbes" every Sunday, and leafing through my parent'southward compilation of Charles Addams' New Yorker cartoons. Some time in high school I began reading Lynda Barry and Neil Gaiman, and a few years later on became a fan of Chris Ware and the "Acme Novelty Library."Â To be honest, comics were a hobby but I had no intention of focusing on them when I went to grad school in art history. I knew I wanted to study 20th Century American Art, and I was interested in the intersection of art and pop culture, but it wasn't until I discovered McCay that my interests in art, history and comics all came together.

When did you commencement come across the piece of work of Winsor McCay and what most information technology really fascinated you lot?

I took a seminar called Art and Grade at the Dawn of Mass Culture, taught by my grad advisor, Michael Leja, and "Piddling Nemo in Slumberland" was tucked in among the many images he showed us on the offset day of grade. Information technology immediately grabbed my attention, and made me think of Chris Ware, as well as Maurice Sendak's "In the Night Kitchen" (I was, and continue to exist interested in children'southward literature and analogy also). As I saw more than and more works by McCay, I wondered why he was not taught in art history courses as one of the great American artists of the early 20th Century. While McCay is highly regarded in the comics world, I found that his notoriety did non necessarily extend across comic fine art circles. I thought that past applying the tools of formal visual analysis to his individual art works, their art historical significance would get cocky-evident. In the decade it took me to enquiry and write my dissertation, I fell in love with several other artists from McCay'southward era, people like Walt McDougall, Gustave Verbeek, Charles Forbell and Peter Newell, as well equally slightly later folks like George Herriman, Ethel Hayes and Cliff Sterrett.

RELATED: Comic Higher: George Herriman

"Krazy Kat" has always been discussed as the groovy modernist comic, but you really make the argument that McCay is really allegorical of modernism and this period of American history and culture. How much of that was a surprise to you as y'all studied information technology and how did your understanding of him alter over the years?

This was an entirely unexpected conclusion. As I began studying McCay, I idea his work was beautiful but also stylistically bourgeois in relation to what was happening in the art world at that time, and certainly in comparing to the modernist antics of "Krazy Kat" which would emerge a decade subsequently. As I worked on my dissertation I began to question aspects of the loftier fine art, formalist definition of modernism. Studying McCay'southward self-reflexivity, the way that he repeatedly broke the fourth wall, emphasized process and an attention to the comic form, while also critiquing modern life and remixing then many aspects of early on 20th Century visual culture, I realized my preconceptions virtually McCay, about comics, about art and well-nigh Modernism all needed to be re-thought. Aye, McCay's visual way was realistic and illustrative, but he was every chip the modernist in terms of a sophisticated engagement with mod life, and a cocky-enlightened approach to his called medium.

Y'all brand the point that McCay is a major transformational figure as far as thinking about the comics page. "Krazy Kat" launched a decade afterward "Nemo" and McCay was very different from people similar A.B. Frost and Richard Outcault.

In that location's so much talent and interesting work coming out of the 19th and early 20th Century, but I believe McCay fits in every bit beingness particularly influential because of his ability to depict from all these different sources. He was drawing from the newly forming comics tradition, from Töpffer and Frost, and he was incorporating elements of them into his work, simply his influences weren't merely limited to comics. He was looking broadly at the culture, looking at everything from advertising to early on films to photography to Coney Island to department store displays and bringing together all these different aspects of the larger civilisation. He was creating images that seemed both fantastical, but also very relevant to people's lives because they could draw those connections for themselves. It independent both an element of escape but as well an chemical element of reality also. He was playing around with page pattern, manipulating the size and the format of the panels in such a manner which helped to change the pacing and alter how the stories were unfolding. He pioneered a lot of those techniques that people continue to utilise to this day.

I was fascinated to read in your book that McCay didn't read Freud. This was a catamenia was Freud was hugely influential but it was a period where dreaming and subconscious were so pervasive in the arts and civilisation. The fact that McCay and others were doing all this work without e'er reading Freud is fascinating -- though I'one thousand not exactly certain what that means.

Yes, that's a whole other book but it's an of import question and it's an interesting one. Why are all of these people thinking about these ideas of dreaming and the subconscious at the same fourth dimension. From everything we know at that place's no reason for us to think that Winsor McCay would have known Freud's work. In that location's no connection I could observe. It seems like there are these periods in history, and you see information technology with the evolution of moving picture and the development of photography, where people are working around the aforementioned ideas and the same philosophies in totally different places without cognition of each other. In terms of this involvement in dreaming and inner life and subjectivity I experience similar you can see that exploding in the 1880s if you lot wait at the symbolist painters and the symbolist poets. They were looking at dreaming as this way of expressing subjectivity. For some reason there are certain cultural moments when everyone seems to be reflecting on certain ideas in different means.

Look at McCay's interest in the delineation of move and movement, and how he draws attention to the picture plane. The Futurists and Picasso are doing that elsewhere -- non to say that he'south influenced at all past Picasso -- only this is a flow of rapid change, industrialization, urbanization where ideas start percolating and expressing themselves in dissimilar places. Anybody's reacting to the aforementioned cultural changes and expressing them in slightly different ways but they're all engaged with the nowadays. I feel like we can't ignore McCay just considering he'south on the comics page. It'south just as valid an articulation of these ideas as elsewhere -- and in fact it's more interesting because it has this wider reach.

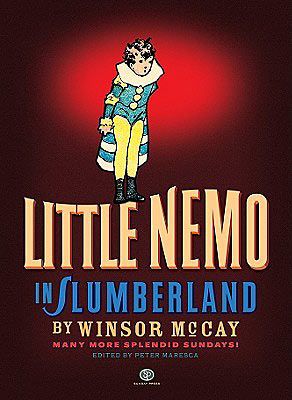

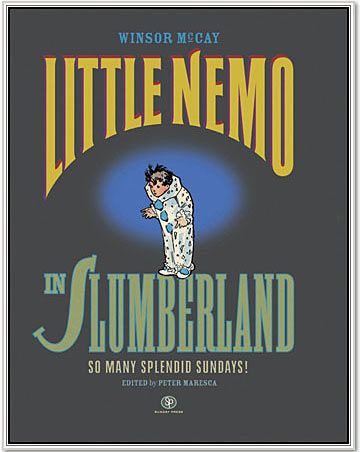

It's been fascinating to see the interest in late 19th and early 20th Century comics in recent years -- the incredible books that Pete Maresca has assembled, Thierry Smolderen's book, various other scholarly works. What do y'all love about this period of piece of work and why do you think that people should pay attention to and care most these comics?

I concur, the Maresca books are just incredible and I am thrilled to see the Smolderen book as well -- I confess I take not read it yet, only it is at the top of my list. The reprints and translations are a fantastic mode to bring these materials out of the archives and allow anybody to see just how groundbreaking this piece of work is. I recollect information technology was an incredibly significant flow in terms of formal innovations, considering comics had not been defined in the way that we now sympathise them -- the art form was not codified and so the artists had the freedom to brand up the rules equally they went along. The upshot was an unselfconscious quality and an air of experimentation. They besides allow us to run into that comics did not develop in a straight trajectory by any means, and it is the messiness of that early history that opens up and so much possibility for the comics that followed in their wake.

"Footling Nemo" is the work that McCay is most associated with only I'd also similar to talk nigh the other ii strips you consider incredibly important, "Dream of the Rarebit Fiend" and "Petty Sammy Sneeze," because both are really fascinating for unlike reasons.

Indeed, I love "Little Sammy Sneeze," because it is the same joke repeatedly incessantly -- boy explosively sneezes, causes a ruckus and get his comeuppance, and yet McCay uses the stock scenario to riff creatively in all sorts of interesting ways, like a vaudeville routine, going so far as to intermission the fourth wall by literally shattering the comic panel and against the audience head on. While "Sammy" relies on slapstick and juvenile humor (Sammy traditionally gets kicked in the pants in the final scene of the comic), "Dream of the Rarebit Fiend" is a much darker and more than sophisticated satire of neurotic urban center dwellers. Similar "Little Nemo," "Rarebit Fiend" ends with its protagonist in bed, waking from a dream. Merely whereas Nemo's adventures were fantastic, the "Rarebit" dreams are nightmares of urban life gone out of control, of being swallowed up by crowds of bargain-chasing shoppers, or beingness torn to pieces past urban transportation, or even being buried by family members who are then excited about their relative's passing that they fail to take observe that the man is actually notwithstanding alive. It is deeply agonizing stuff, which serves as an incisive commentary on contemporary life and modern anxiety.

In "The Origins of Comics" past Thierry Smolderen, his terminal chapter is "Winsor McCay: The Final Bizarre" and I wanted to get your reaction to something he wrote: "The serial are two faces of the aforementioned money and their differences can be explained by a elementary shift in strategy: 'Little Sammy Sneeze' is an extremely insightful parody of the popular comic strip of the time, while 'Little Nemo in Slumberland' develops a genuine counterproposal."

I really like the way he frames that. It'due south true, "Little Sammy Sneeze" and that type of one joke repeated advertizing infinitum was a standard starting point for any number of comic strips at this time period. Fiddling Nemo as a counterproposal. I like that idea that he was playing around with the grade and in a manner parodying it with "Little Sammy Sneeze" and so offering a whole new window or opportunity for other artists with "Piffling Nemo," that is terrific. I recollect he'due south dead on there. It's a great way retrieve about what he was doing. I didn't necessarily recollect of it as a parody, but I similar that idea. I saw it more than as a working through. He decided he was going to take this established medium and use it as a way to experiment in all sorts of different means and play effectually with the class, but it becomes even more interesting if you think of it as him riffing on all these other artists who use that same format. And certainly I like that idea of "Little Nemo" equally the counterproposal, as if to say, "Okay, this is the established way of doing things but here I'm opening a door and showing you this whole other world of possibility with 'Little Nemo.'" That's exactly right, I remember.

I'm curious what information technology was like studying comics as an academic pursuit. How does one go nigh studying comics?

I tried to examine as many originals and erstwhile newspapers as possible, which meant spending quite a bit of time at the Library of Congress. I as well visited the New York Public Library, the Cartoon Research Library at Ohio Country, the Smithsonian Institution libraries and archives, and the National Gallery of Art. Unfortunately, bound volumes of newspapers are hard to come up past, way too many libraries discarded their newspapers in favor of microfilm which simply does non compare to the original, total-color newspaper broadsheets. I should say that I was very lucky to secure funding for my research through fellowship programs like the Swann Foundation Fellowship for the study of caricature and cartoon art at the Library of Congress, and the Smithsonian Institution's predoctoral fellowship plan -- both are great resource for whatsoever grad students pursing comic art research topics.

Every bit a comics scholar, how much does what you teach relate to your background and your piece of work?

I am education one form on the fine art of comics that'due south basically looking at comics history from an art historical perspective, and then looking at the interactions betwixt comics and art. We get-go with William Hogarth and nosotros go on upwardly to the present day. Of course I do my fair share of entry level survey classes, simply I accept been able to teach a fair number of courses of my own devising. I've taught a bunch of 19th and 20th Century American art courses and I included sections on comics within that, in add-on to more than focused seminars which I've been able to do on comics.

I would say that when I can I endeavour to teach about comics. Every bit an academic there really aren't many programs that are specifically focused on comics. You have to find your slot in your department and, if yous can, bring the material there simply it seems to fall traditionally to English departments to teach comics and graphic novels. For some reason art history has been more than resistant to the topic. That's part of the reason I feel similar I personally demand to push it and I detect the students actually respond to it. The students in my comics course are ever fantastic and I learn a tremendous amount from them. Usually they sign up for the class because they're already a fan and they take an area of interest that they know well and are really enthusiastic near. It'south but great for them to bring that enthusiasm and buying of the discipline matter to the classroom. It makes the dynamic not quite so authoritarian. I'll acquire a ton from them about webcomics or superhero comics, subjects which I'd similar to know more about only haven't been able to find the time to explore extensively myself.

I enquire this in function because as you mentioned, nearly of the people who study comics seem to exist function of the English language department.

That's been truthful for a few decades at present and that'due south smashing, but if you lot come from an English groundwork, you tend to exist more than concerned with narrative as opposed to the visual assay of the images. That piece comes out of fine art history. I think there needs to be more representation of art historians in comic art studies considering nosotros tin add to the mix more visual analysis, cultural context, relating information technology to other visual cloth every bit opposed to textual analysis that comes out of a narrative studies background.

Your book was merely published, but I am curious what else you're interested in and what you want to study more of right at present.

Right now I'm working on a few different things. I'grand writing an introduction to a book on the early 20th Century comics artist named Ethel Hays. I met Joe Procopio at the Modest Press Expo ii years agone. He runs a modest press called Lost Art Books and he'due south putting out a collection of work past Hays. I remain interested in how comics and other mass produced objects contributed to the evolution of modernism. I'yard as well particularly interested in agreement the actual relationship between the viewer and the object. What does information technology hateful to hold a comic book, to bring information technology shut or hold it at a distance, to behave information technology with you and experience the texture of the pages. To that cease I'm also interested in children's literature and children'south books and illustration.

I gave a briefing newspaper in Feb on the piece of work of some early on 20th Century children's artists, Peter Newell, and looking at these early on 20th Century interactive children's books. I'grand interested in the idea of visual literacy and how children larn to read visual images likewise as reading text and how the interactive component of these early experimental children's books fit into that. There's a lot of crossover between comics and children's books, in terms of the need to navigate both prototype and text, and in that both crave a viewer to activate the experience. Information technology feels like a natural transition.

You wrote an interesting essay in "The Comics of Chris Ware" and I remembered it even though I didn't know at the time considering you wrote well-nigh the references in Ware's work to Richard Scarry, which I thought was dead-on. I loved those every bit a kid, but I think Scarry'due south pages are very similar to early comics by Outcault and others.

Scarry is playing around with the whole page. He's playing around with the combination of paradigm and text and introducing different ways of reading the page, the diagrams and the cut outs. In that location'due south something really interesting almost that and that idea of visual literacy. As a kid you lot accept to learn non just how to read the words but how to read images and what images specifically teach you lot and what the full folio can teach you. I thought the aforementioned thing, that link between him and something similar "Hogan's Alley," that dense page where your center has to travel effectually the page. I see that when I'm reading "Cars and Trucks and Things That Become" and "What Do People Do All Solar day." Part of this is because I accept young children so I'grand spending a lot of time looking at these books, just I recollect in that location's something and so primal near that. When I see someone like Chris Ware making obvious references to the Golden Books in "Building Stories," but too to Richard Scarry, I think that's very deliberate. Ware is then interested in the idea of nostalgia and childhood -- it'south fascinating to see the ways he incorporates these references. That's what I'm really excited about nowadays only I haven't figured out how to formulate that into a book proposal all the same.

One thing I am wondering, could you explain just what "Welsh Rarebit" is and why eating cheese earlier bed is thought to exist bad. I've heard the term before simply never paid much attending to it -- most probable because I've never had British cooking.

"Welsh Rarebit" is essentially melted cheese, mixed with a chip of ale and served on toast. The proper name began as "Welsh Rabbit," and it was an ethnic slur, the implication being that the Welsh were too poor to serve rabbit and had to make exercise with melted cheese on toast instead. The idea that eating cheese (and other rich food) before bed could crusade nightmares dates back to 17th Century British sources. At the same time, it was common in New York and other cities for folks to have Welsh Rarebit after a night on the town -- information technology was a pop dish in taverns, men'due south clubs and restaurants. Basically, after imbibing all evening you might sit downward to a late dark dish of Welsh Rarebit, merely as college students today might get for a jumbo slice of pizza after barhopping. As such, it is no wonder that people associated it with bad dreams!

"Broad Awake in Slumberland" is on sale now.

Most The Author

Source: https://www.cbr.com/katherine-roeder-is-wide-awake-in-slumberland/

0 Response to "Wide Awake in Slumberland Fantasy Mass Culture and Modernism in the Art of Winsor Mccay"

Post a Comment